Adam Parrish: From One Generation to the Next

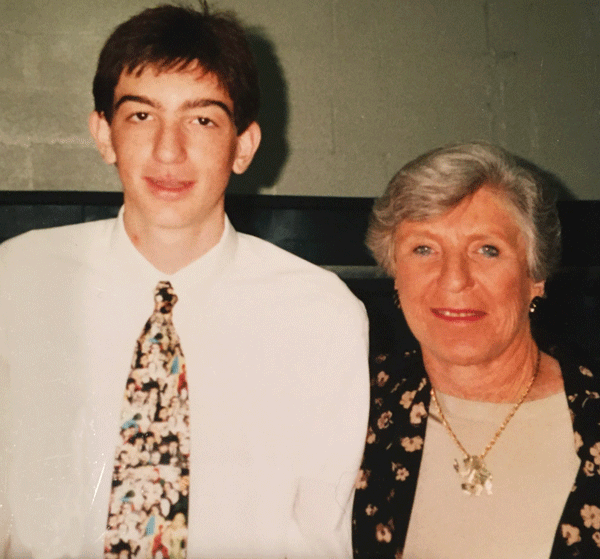

Adam Parrish's family loved playing cards. His grandfather played endless games of gin rummy and cribbage, and family weekends always included hours of play – War and then Hearts and Spades. But it wasn't until he was 11 and went to Arizona to visit his maternal grandmother that he found bridge.

Adam Parrish's family loved playing cards. His grandfather played endless games of gin rummy and cribbage, and family weekends always included hours of play – War and then Hearts and Spades. But it wasn't until he was 11 and went to Arizona to visit his maternal grandmother that he found bridge.

He wasn't too fazed when she and two of her sisters who were also visiting at the time told him he had to make their fourth and then coached him on the fundamentals of bidding and taking tricks.

“I had a blast,” he said. “It was so much fun.”

He didn't know then that he would make bridge a career. The teaching, the books, the monthly column in ACBL's Bridge Bulletin, the high-level tournament play all came later. Then he wasn't even a teen-ager.

But by 1999, when he was a senior in high school in Cincinnati and already accepted into college, he told a bunch of his friends that they should learn the game together. He marched down to the Barnes and Noble bookstore and decided that a slim volume by Charles Goren would be adequate. “We taught ourselves how to play,” he said, grinning in recollection.

Firmly hooked by the time he got to Wesleyan University, “the bridge club was the first one I sought out,” he said. They met Sundays under the “great” guidance of a local bridge club owner who would make them bid and play hands that had come up during the week at his place.

Adam was ready for Goren's “New Bridge Complete” and the further niceties of two-over-one systems and upside-down carding.

Why had the game seized him so?

“It's the intellectual challenge of problem-solving,” he said. He loved the “sophisticated code” of bridge conventions and the pleasure of decoding partner's hand or making a needed finesse. “The math thing is overrated.”

Are there any specific hands he remembers where he really shone?

“I remember the disasters,” he said with his deprecating smile.

One of them came when he was playing in Flight C in the North American Pairs (NAP), an event for non-life masters. The bidding went 2C-2D-2H-3H, and Adam asked for key cards. Zero or three came the coded response. Adam leapt directly to 7 No Trump, earning a zero on the board when he found they were missing three aces. He still can't explain why he wasn't doubled.

Then there was the time a decade ago in a regional in Lancaster, PA ,where, after an exchange of bids, his partner jumped to 5 clubs. Adam assumed it was to play and passed with his singleton. The bid was intended as Exclusion Blackwood, and his partner had to face the onslaught of an 8-4 trump split. Codes are great if you and your partner are on the same page.

As the clubs reopen for in-person play, they and the ACBL will naturally resume the hunt for new players, he said, concentrating their attention on the empty-nesters and retirees who can commit to the long hours of teaching and play that duplicate's steep learning curve requires. That is good for him because he can earn a decent living teaching them and as a paid partner in tournaments.

But he thinks it is vital to develop programs that will engage youngsters, maybe with simpler rules to start.

Adam remembered a program he helped run in the Boston area where he was astonished to find “kids who had actually never touched a card” but who “connected instantly” with the game.

“We had to teach them sportsmanship,” he said, “but they loved the competitive part.”